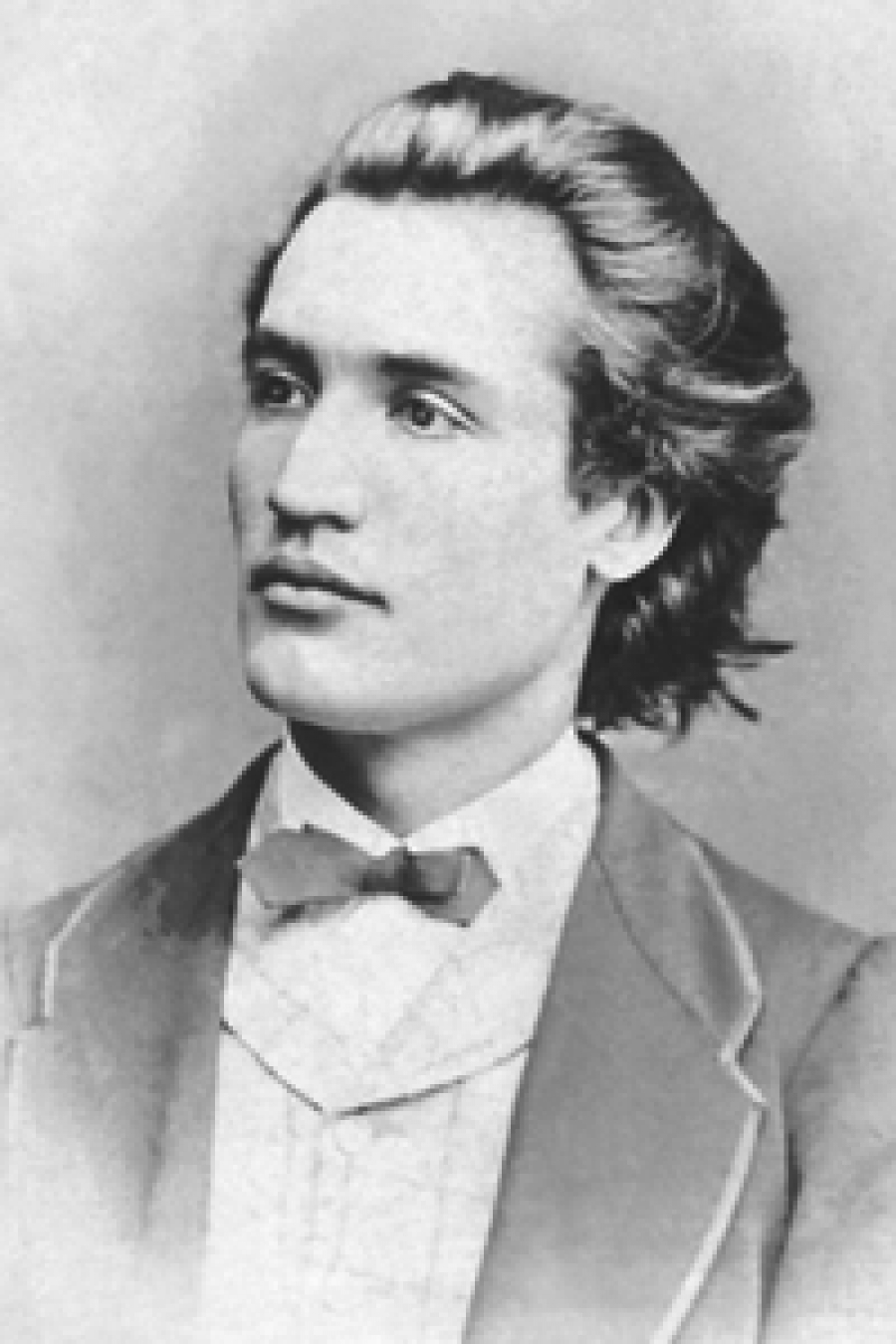

Born in 1951; graduated in law, specialisation in economics (Erasmus University Rotterdam, 1973); Doctor of Laws (University of Utrecht, 1981); Researcher in European law and international economic law (1973-74) and lecturer in European law and economic law at the Europa Institute of the University of Utrecht (1974-79) and at the University of Leiden (1979-81); Legal Secretary at the Court of Justice of the European Communities (1981-86), then Head of the Employee Rights Unit at the Court of Justice (1986-87); Member of the Legal Service of the Commission of the European Communities (1987-91); Legal Secretary at the Court of Justice (1991-2000); Head of Division (2000-09) in and then Director of the Research and Documentation Directorate of the Court of Justice of the European Union (2009-11); Professor (1988-2003) and Honorary Professor (since 2003) in European law at the University of Maastricht; Adviser to the Regional Court of Appeal, ’s-Hertogenbosch (1993-2011); Member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (since 1993); numerous publications on European law; Judge at the Civil Service Tribunal since 6 October 2011.

First of all we would like to thank you warmly for accepting this interview.

1. As a first question, we would like to ask you to provide a short description of your formative years in law, which is certainly very useful to “apprentices” in law.

That was before the present ‘BAMA’ system. After four years of study at what is now called the Erasmus University Rotterdam (NL), I obtained my academic degrees in law and in economics (1973).

2. How would you assess your main professionalperiods? Which of them was the most challenging?

In other words, we would like to ask you about your professional experiences at the EU courts. For a significant period of time, you have acted as legal secretary at the Court of Justice. Therefore, you are very familiar with the EU judicature. What models do you have among the members of the EU courts?

I worked for five years for an advocate general, followed by five years at the Legal Service of the Commission and after that for nine years for a CJEU-judge. Every period was a challenging one since it allowed me to work from different perspectives on the same problems.

I have no models among members of the EU-courts; however I learned a lot from Pieter Verloren van Themaat, the first Dutch advocate general at the CJEU, for whom I worked from 1981 to 1986.

3. From your point of view, what would be the mainchallenges for the current European Court of Justice?

To integrate the Fundamental Rights Charter into EU-law to the extent that the rights and principles contained in the Charter become the main source of inspiration of the ECJ’s case law.

4. Could you please comment on the most importantrecent developments concerning the EU legal order – from your point of view?

The main threat to the EU-legal order is the fragmentation caused by intergovernmental treaties (ESM, Budgetary Discipline) and practices which, since they are concluded between less than 27 member states, risk to create distortions that in the long run might affect the unity of the internal market. The same threat is caused by the absence of effective measures to combat the euro-crisis and the shifts in the institutional equilibrium of the EU. Without an efficient economic and monetary union you cannot have an internal market. In other words, there is no alternative to a ‘federalisation’ of the EU, either in its present form or as a nucleus of a number of continental member states.

5. What does it mean the “Autonomy Of [EuropeanUnion] Law” from the point of view of Post-Lisbon developments and more generally for the developments of constitutionalism at EU level?

Autonomy of EU-law means nothing more than that EU-law itself stipulates (through its courts) how it is to be interpreted and to be applied. Only on that condition EU-law can be applied in every Member State on the same conditions, which is a necessary requirement for its effectiveness in terms of Articles 2 and 3 TEU. Because EU-law (according to the case law) is autonomous, it is also constitutional, since it sets its own standards of effectiveness and legality. Autonomy of law reflects that in a period of globalisation, the state is no longer the sole source of law, in spite of what constitutional courts might rule. It reflects that the centuries old link between state, territory and law is coming to an end.

6. What is the relationship between EU Courts in“saying the law”? Does the “lower” EU Courts - CST and GC – follow a “self-restraint” attitude (or deference) towards the “higher authority” – the ECJ?

It seems obvious to me that you look for precedents in the case law of the superior courts. However, I have no difficulty in defending an opposite solution if necessary. There is certainly ‘respect’, but no ‘deference’ or ‘fear’ (to be annulled).

7. What is the role of documentation (and moregenerally) of legal doctrine in EU Courts decisions?

The role of legal doctrine in EU courts decisions is very limited. The influence of the case law on legal doctrine is far greater. In my opinion, that is the way it should be. If not, we would not have direct effect, no primacy, no direct effect of directives, no state responsibility and many other things.

8. What would be the limits – if any – concerning the academic opinions expressed by Judges? In this context, which is your point of view on dissenting opinions; is this a kind of “knowing for the sake of knowing” (as in case of concurring opinions) or could that lead to a genuine familiarisation with the ECJ as a whole?

As far as their composition is concerned, the EU courts are international tribunals. Once you introduce dissenting opinions, it will only be a question of time before member states are trying to influence the attitudes of ‘their’ judges’. Do not forget that the EU is not a state or a federation.

As a member of a court you should be cautious in what you say (in public) and what you write. In my opinion you cannot defend a particular point of view which is not accepted, now or later, by the court of which you are a member since that would be incompatible with your duty to keep the secret of the deliberations.

9. A final question: Which advice/recommendationwould you give to young researchers in (EU) law?

First, learn your languages, at least two.

Second, stay abroad to study or to work.

Three, keep yourself informed not only about legal developments (that is obvious), but also about political events and trends.

Fourth, when you are young, every day, week, month or year counts twice for your future.

Thank you very much.

Interviul face parte din lucrarea ”Interviewing European Union. Wilhelm Meister in EU law”, Coordonatori: Daniel Mihail Sandru și Constantin Mihai Banu, Editura Universitara, 2013

http://www.editurauniversitara.ro/carte/sandru/interviewing_european_union_wilhelm_meister_in_eu_law/10468