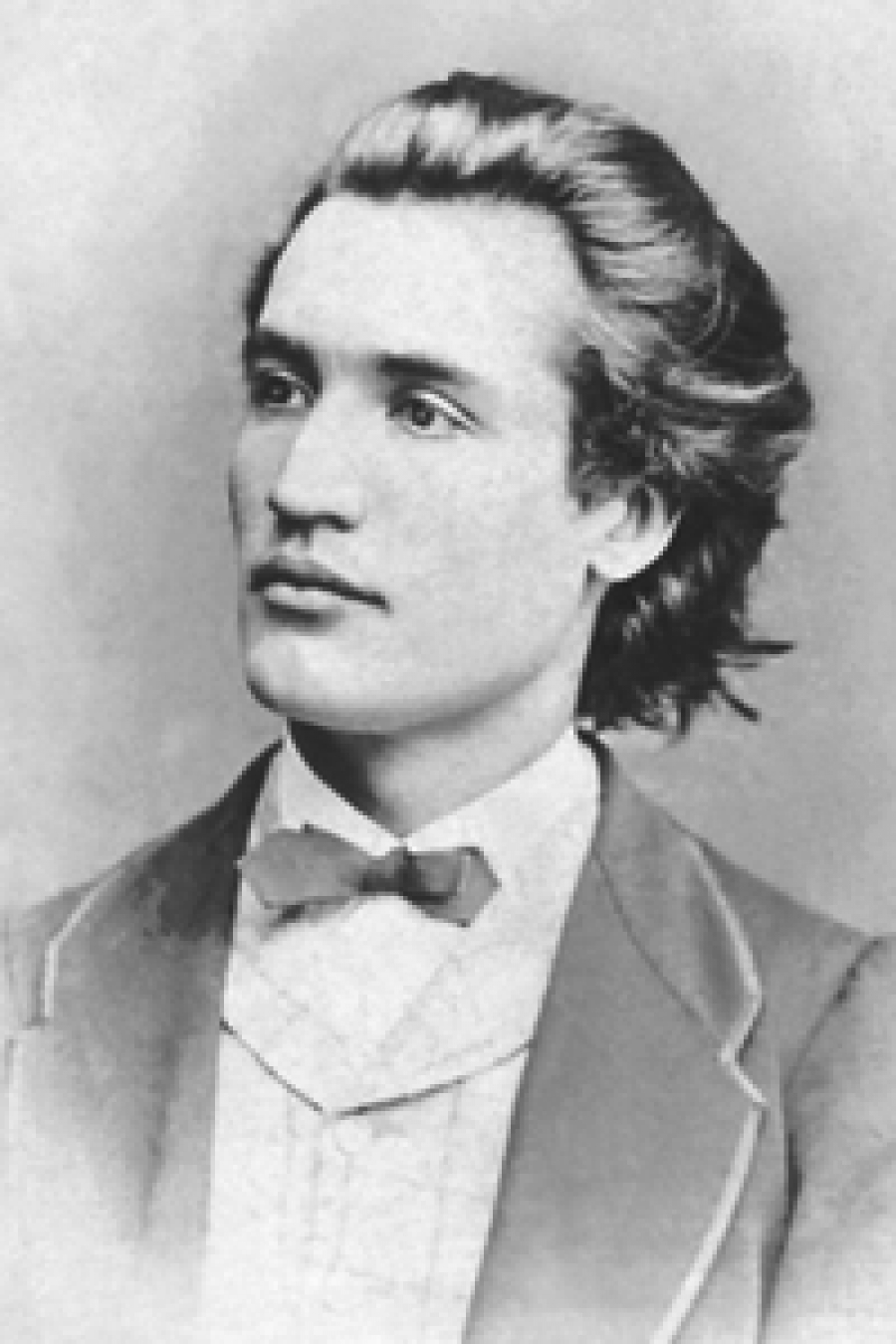

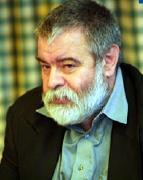

Professor Patrick Birkinshaw has been a professor since 1990, and has lectured at University of Hull since 1976. He is Director of the Institute of European Public Law (University of Hull), and has been Editor in Chief of European Public Law since 1995. He has written various books including Government and Information: the Law Relating to Access, Disclosure and Regulation (3rd ed 2005), European Public Law (2003), Freedom of Information: the Law, the Practice and the Ideal (3rd ed 2001), Grievances Remedies and the State (2nd ed 1995) and Freedom of Information: the Law, the Practice and the Ideal (4th ed 2010 Cambridge University Press). Professor Birkinshaw worked as a specialist adviser to the Commons Public Administration Select Committee in its enquiry into ‘Political Memoirs’ in 2005/2006. He has acted as a government and parliamentary adviser and has represented the UK in international legal seminars. From 1997 until 1999, he served as a specialist adviser to the House of Commons Select Committee on Public Administration in its review of Government proposals, and its Bill on Freedom of Information. Professor Birkinshaw is also on the Senior Schemes’ Assessment Board for the Irish Research Council for Humanities and Social Science, which allocates public funds for academic research.

First of all, we would like to thank you warmly for accepting this interview.

1. As a first question, we would like to ask you to provide a short description of your formative years in law, which is certainly very useful to “apprentices” in law.

I started studying law in 1972, at the University of Hull. Before that I had studied an English literature degree in London but left that study after a year. After graduating in law, second in my whole year, I studied at the Inns of Court School of Law in London to become a barrister. I was called to the Bar of England and Wales in July 1976 at the Inner Temple. I commenced lecturing in law in October 1976.

2. You have a specific academic background, coming from the common law world. Could you please provide us with a brief insight of the looking glass employed in comparative law (related to EU legal order) by a professional familiar with the common law?

I came to EC/EU law rather late. I began to concentrate in English Public Law in 1977. By the late eighties I was asked to be the national rapporteur for the UK on Public Procurement at the FIDE conference in Madrid in 1990. My role on this project made me realise that if one were not knowledgeable about EC law, one’s knowledge and expertise in domestic Public Law would be extremely limited. In 1994, I became editor of the newly established journal European Public Law (KLI) which commenced publishing in 1995. It is now approaching its nineteenth year of publication.

3. What should a professional from a new Member Stateof the EU learn from experiences of the UK as an older Member State?

Learn to be flexible and open minded and receptive to new ideas.

4. We are not going to ask you about the (historical) “incoming tide” on the UK legal order brought by the (then) EC law (as once put by Lord Denning). Instead we would like to ask you to comment on the recent developments concerning the (legal and constitutional) position of the UK in EU legal order?

There has been deep unpopularity with the EU and ECHR projects among the Conservative Party, the press and a wide section of the UK public. Much of this is based on ignorance. The European Union Act 2011 seeks to establish the primacy of domestic law via Parliamentary Sovereignty. The Act also provides for national referenda on most EU developments affecting the UK – ie Treaty ratification, etc. Ironically, the resort to referenda is likely to diminish the pristine sense of Parliamentary Sovereignty. At the moment, the British public is unlikely to approve new treaties. There is an opt-out from a referendum within the Act which may well cause legal difficulties before the UK courts.

5. On the other hand, we would like to ask you tocomment on the trends pertaining the public/private law division.

It’s a huge story. Public law was almost unknown in England in 1960. A revolution started in the early 1960s which is still continuing. We now have an Administrative Court of the High Court and a comprehensive tribunal system in the UK introduced by the Courts, Tribunals and Enforcement Act 2007.

6. In your opinion, what are the most importantdevelopments brought by the Lisbon Treaty, more than two years since its entry into force?

Accession to the Council of Europe will be very important. The Charter of Fundamental Rights and its recognition as a fully enforceable legal provision is crucial – the UK has not opted out of the Charter as was widely, and incorrectly, reported. Bringing the Third pillar within the Community method is very important although the UK has opted out of significant provisions. Setting out the powers of the Union and states is a clear advantage.

7. You have extensively published in the field of accessto information, concerning both the UK regime and EU rules. Therefore, we would like to ask you to comment on the recent developments at the EU level, more precisely on the case-law of the EU courts (General Court and Court of Justice). Is the more recent case-law of those courts a mark of a more transparency? Or the contrary position is taking shape?

I think the case law is mixed – some good some bad. We still await the new regulation on access. The Commission had some questionable reforms that will not advance transparency. The interesting thing is how greater transparency is affecting our national judges, particularly under the influence of the European Convention on Human Rights.

8. You acted as an advisor at certain Parliamentary committees. The UK has a major culture concerning the use of professional expertise (hearings, reports and so on) in Parliamentary works. Therefore, what is the role of that expertise in the law-making and Parliamentary scrutiny concerned matters connected to EU law? What lessons should be drawn from the UK experiences in a comparative perspective (to other Member States of the EU)?

I worked on the Public Administration committee in its review of proposals for Freedom of Information legislation (1997-2000) and then maintaining confidentiality among ministers, ambassadors and civil servants and private advisers (2006-2009). The House of Lords Constitutional Committee has a full time specialist adviser who is a public lawyer and the committee may report on EU related matters affecting the constitution. However, the Commons and Lords specialist committees as far as I know do not have specialist advisers but the latter calls for evidence and I have given that on several occasions. The specialist adviser can have profound influence on the report of the committees. It depends. If the government accepts the report, that will obviously influence legislation.

9. In the end, what is the life of an Editor-in-Chief at a major law journal (i.e. the European Public Law, edited by Wolters Kluwer)?

We have many submissions and life is very busy!

Thank you very much.

Interviul face parte din lucrarea ”Interviewing European Union. Wilhelm Meister in EU law”, Coordonatori: Daniel Mihail Sandru și Constantin Mihai Banu, Editura Universitara, 2013

http://www.editurauniversitara.ro/carte/sandru/interviewing_european_union_wilhelm_meister_in_eu_law/10468